Sir Thomas Burke in the 18th Century Ireland

Sir Thomas Burke (1750-1813) stands as a multifaceted figure in 18th-century Irish history. Born into a Catholic landowning family in County Galway, he navigated a complex social and political landscape with ambition, a keen awareness of the changing times, and a compassionate spirit. His life story intertwines themes of land management, religious tolerance, and a commitment to progress, all while offering a glimpse into the plight of displaced Catholics during a tumultuous period.

From Heir to Innovator

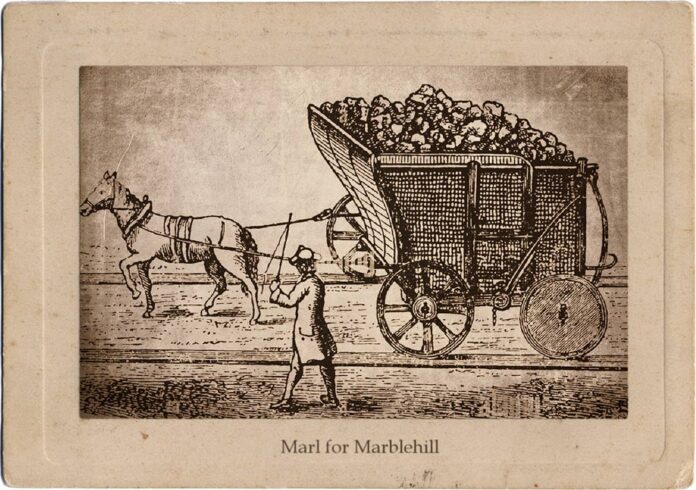

Inheriting a substantial estate, including the grand Marblehill mansion, from his father in 1793, Sir Thomas wasn’t content with simply maintaining the status quo. A shared passion for agriculture with his father fueled a drive for improvement. He actively pursued land reclamation projects and experimented with innovative techniques like using marl fertilizer to revitalize mountain land. His dedication to tree planting stands out as a remarkable example of his environmental consciousness.

Large-scale planting on 42 acres earned him bounties from the Dublin Society, a testament to his contribution to Ireland’s landscape. While some questioned his methods, Burke’s commitment to improving the land garnered widespread approval, particularly for his extensive tree planting initiatives.

Balancing Loyalty and Identity

Sir Thomas skillfully navigated the often-fraught relationship between the Catholic community and the British government during these times. His unwavering loyalty to the crown was evident in his willingness to become a magistrate following the Catholic Relief Act of 1792, a pivotal moment that granted some rights to Catholics.

The authorities recognized his value as a bridge between the two communities, rewarding him with a baronetcy in 1797. This prestigious title elevated his social standing and solidified his reputation as a man of influence. His support for the government was further demonstrated by his signature on a loyalty petition during a politically turbulent period. However, claims suggesting his advancements were solely due to a later marriage to nobility were unfounded – the baronetcy predated the union by two years.

A Haven in the Slieve Aughties

The mid-1790s saw a mass displacement of Catholic families, particularly in Armagh, Ulster. Faced with hardship, many sought refuge elsewhere. Sir Thomas, ever the resourceful landowner with perhaps a sense of social responsibility, stepped in to offer sanctuary. He leveraged his recently acquired Slieve Aughty Mountains estate to create a haven for these displaced Catholics from the north. This act of compassion served a dual purpose – it provided a safe haven for displaced families while also creating a willing workforce for Burke’s ambitious agricultural plans.

These plans included extensive afforestation projects, echoing his earlier tree planting initiatives, and the construction of high-quality roads using refuse from nearby ironworks. This innovative approach to road building further solidified his reputation as a man who embraced progress.

Family and Legacy

Sir Thomas married Christian Browne in 1774 and together they had seven children. His loyalty to the crown was further solidified when he offered to raise a regiment in 1804, led by his son, Colonel John Burke. Sir Thomas died in 1813, leaving behind a legacy of agricultural advancements, social influence, and a commitment to his family and faith. He embodied the spirit of progress in 18th-century Ireland, leaving a lasting mark on the land and the lives of those around him, including the displaced Catholic families he welcomed onto his estate.

For Further Reading:

- James Hall, Tour through Ireland (1813), vol. i, p. 327.

- Hely Dutton, A statistical and agricultural survey of the county of Galway (1824), pp. 440, 445-446.

- Burke’s Peerage.

- Thomas Sadleir, “The Burkes of Marble Hill,” Galway Arch. Soc. Jn., viii (1913), pp. 3-5.

- P. K. Egan, “Progress and suppression of the United Irishmen in the western counties, 1798-9,” Galway Arch. Soc. Jn., xxv (1952-1953), p. 107.